11,600 BCE to 3,500 BCE — Prehistoric Times

Archaeologists “dig” prehistory. Göbekli Tepe in present day Turkey is a good example of archaeological architecture. Before recorded history, humans constructed earthen mounds, stone circles, megaliths, and structures that often puzzle modern-day archaeologists. Prehistoric architecture includes monumental structures such as Stonehenge, cliff dwellings in the Americas, and thatch and mud structures lost to time. The dawn of architecture is found in these structures.

Prehistoric builders moved earth and stone into geometric forms, creating our earliest human-made formations. We don’t know why primitive people began building geometric structures. Archaeologists can only guess that prehistoric people looked to the heavens to imitate the sun and the moon, using that circular shape in their creations of earth mounds and monolithic henges.

Many fine examples of well-preserved prehistoric architecture are found in southern England. Stonehenge in Amesbury, United Kingdom is a well-known example of the prehistoric stone circle. The nearby Silbury Hill, also in Wiltshire, is the largest man-made, prehistoric earthen mound in Europe. At 30 meters high and 160 meters wide, the gravel mound is layers of soil, mud, and grass, with dug pits and tunnels of chalk and clay.1 Completed in the late Neolithic period, approximately 2,400 BCE, its architects were a Neolithic civilization in Britain.

The prehistoric sites in southern Britain (Stonehenge, Avebury, and associated sites) are collectively a UNESCO World Heritage Site. “The design, position, and inter-relationship of the monuments and sites,” according to UNESCO, “are evidence of a wealthy and highly organized prehistoric society able to impose its concepts on the environment.” To some, the ability to change the environment is key for a structure to be called architecture. Prehistoric structures are sometimes considered the birth of architecture. If nothing else, primitive structures certainly raise the question, what is architecture?

Why does the circle dominate man’s earliest architecture? It is the shape of the sun and the moon, the first shape humans realized to be significant to their lives. The duo of architecture and geometry goes way back in time and may be the source of what humans find “beautiful” even today.

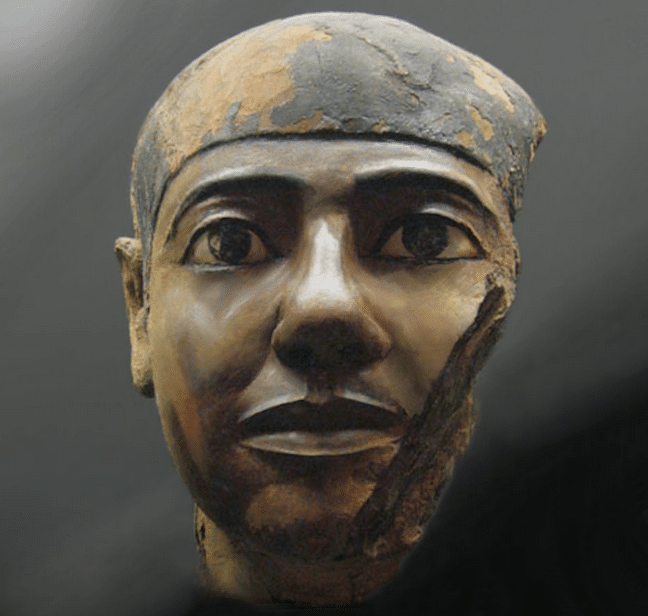

3,050 BCE to 900 BCE — Ancient Egypt

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/pyramid-113282002-crop-58a4e1db3df78c345bc8fafe.jpg)

In ancient Egypt, powerful rulers constructed monumental pyramids, temples, and shrines. Far from primitive, enormous structures such as the Pyramids of Giza were feats of engineering capable of reaching great heights. Scholars have delineated the periods of history in ancient Egypt.

Wood was not widely available in the arid Egyptian landscape. Houses in ancient Egypt were made with blocks of sun-baked mud. Flooding of the Nile River and the ravages of time destroyed most of these ancient homes. Much of what we know about ancient Egypt is based on great temples and tombs, which were made with granite and limestone and decorated with hieroglyphics, carvings, and brightly colored frescoes. The ancient Egyptians didn’t use mortar, so the stones were carefully cut to fit together.

The pyramid form was a marvel of engineering that allowed ancient Egyptians to build enormous structures. The development of the pyramid form allowed Egyptians to build enormous tombs for their kings. The sloping walls could reach great heights because their weight was supported by the wide pyramid base. An innovative Egyptian named Imhotep is said to have designed one of the earliest of the massive stone monuments, the Step Pyramid of Djoser (2,667 BCE to 2,648 BCE).

Builders in ancient Egypt didn’t use load-bearing arches. Instead, columns were placed close together to support the heavy stone entablature above. Brightly painted and elaborately carved, the columns often mimicked palms, papyrus plants, and other plant forms. Over the centuries, at least thirty distinct column styles evolved. As the Roman Empire occupied these lands, both Persian and Egyptian columns have influenced Western architecture.

Archaeological discoveries in Egypt reawakened an interest in the ancient temples and monuments. Egyptian Revival architecture became fashionable during the 1800s. In the early 1900s, the discovery of King Tut’s tomb stirred a fascination for Egyptian artifacts and the rise of Art Deco architecture.

850 BCE to CE 476 — Classical

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/architecture-classical-pantheon-567596451-crop-5ad8dfcb875db90036fb5402.jpg)

Classical architecture refers to the style and design of buildings in ancient Greece and ancient Rome. Classical architecture shaped our approach to building in Western colonies around the world.

From the rise of ancient Greece until the fall of the Roman empire, great buildings were constructed according to precise rules. The Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius, who lived during first century BCE, believed that builders should use mathematical principles when constructing temples. “For without symmetry and proportion no temple can have a regular plan,” Vitruvius wrote in his famous treatise De Architectura, or Ten Books on Architecture.

In his writings, Vitruvius introduced the Classical orders, which defined column styles and entablature designs used in Classical architecture. The earliest Classical orders were Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

Although we combine this architectural era and call it “Classical,” historians have described these three Classical periods:

700 to 323 BCE — Greek: The Doric column was first developed in Greece and it was used for great temples, including the famous Parthenon in Athens. Simple Ionic columns were used for smaller temples and building interiors.

323 to 146 BCE — Hellenistic: When Greece was at the height of its power in Europe and Asia, the empire built elaborate temples and secular buildings with Ionic and Corinthian columns. The Hellenistic period ended with conquests by the Roman Empire.

44 BCE to 476 CE — Roman: The Romans borrowed heavily from the earlier Greek and Hellenistic styles, but their buildings were more highly ornamented. They used Corinthian and composite style columns along with decorative brackets. The invention of concrete allowed the Romans to build arches, vaults, and domes. Famous examples of Roman architecture include the Roman Colosseum and the Pantheon in Rome.

Much of this ancient architecture is in ruins or partially rebuilt. Virtual reality programs like Romereborn.org attempt to digitally recreate the environment of this important civilization.

527 to 565 — Byzantine

/Byzantine-526754246-crop-587273a65f9b584db36e27bc.jpg)

After Constantine moved the capital of the Roman empire to Byzantium (now called Istanbul in Turkey) in 330 CE, Roman architecture evolved into a graceful, classically-inspired style that used brick instead of stone, domed roofs, elaborate mosaics, and classical forms. Emperor Justinian (527 to 565) led the way.

Eastern and Western traditions combined in the sacred buildings of the Byzantine period. Buildings were designed with a central dome that eventually rose to new heights by using engineering practices refined in the Middle East. This era of architectural history was transitional and transformational.

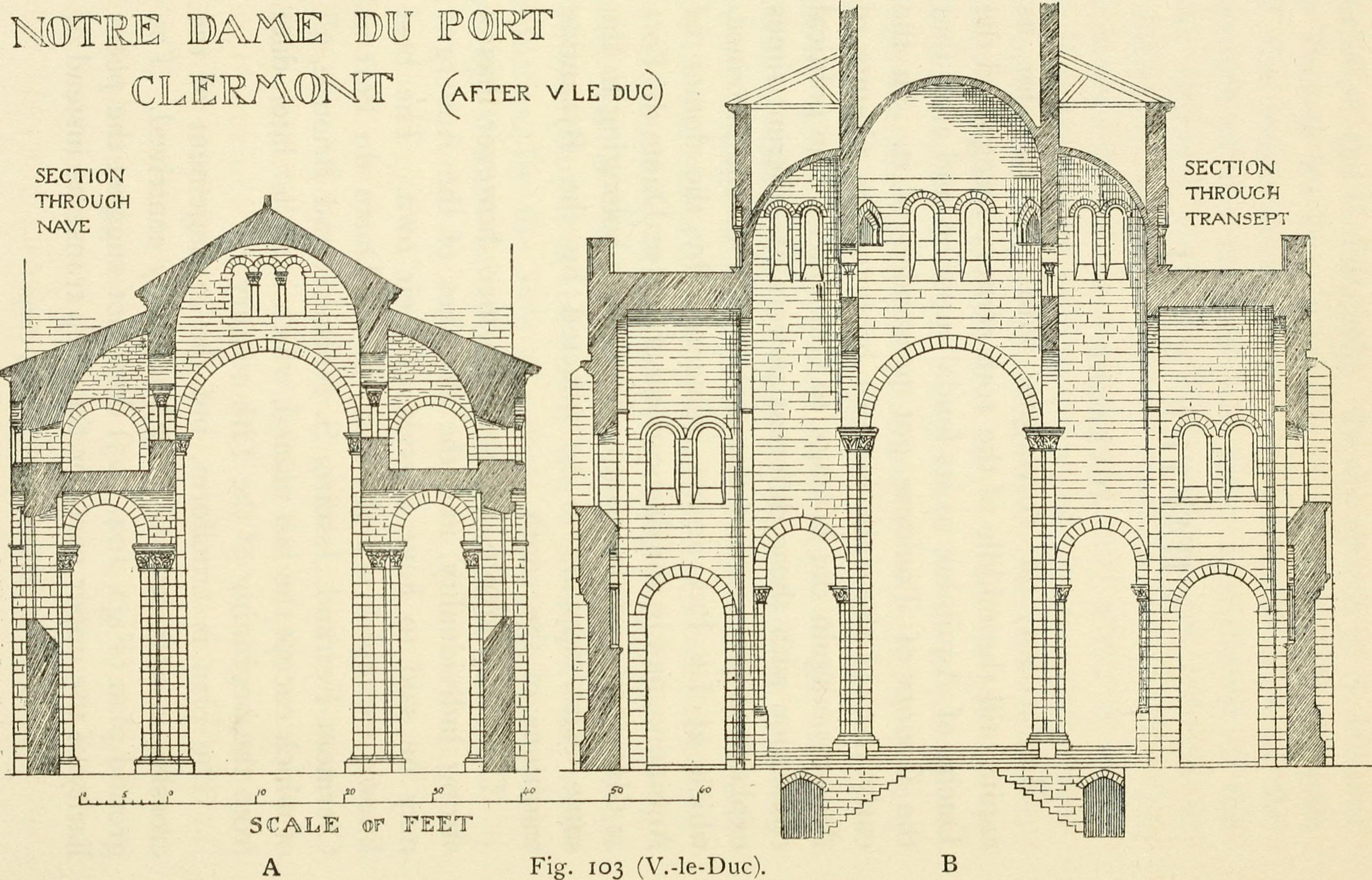

800 to 1200 — Romanesque

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/romanesque-sernin-56a02c4c3df78cafdaa0697d.jpg)

As Rome spread across Europe, heavier, stocky Romanesque architecture with rounded arches emerged. Churches and castles of the early Medieval period were constructed with thick walls and heavy piers.

Even as the Roman Empire faded, Roman ideas reached far across Europe. Built between 1070 and 1120, the Basilica of St. Sernin in Toulouse, France is a good example of this transitional architecture, with a Byzantine-domed apse and an added Gothic-like steeple. The floor plan is that of the Latin cross, Gothic-like again, with a high alter and tower at the cross intersection. Constructed of stone and brick, St. Sernin is on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela.

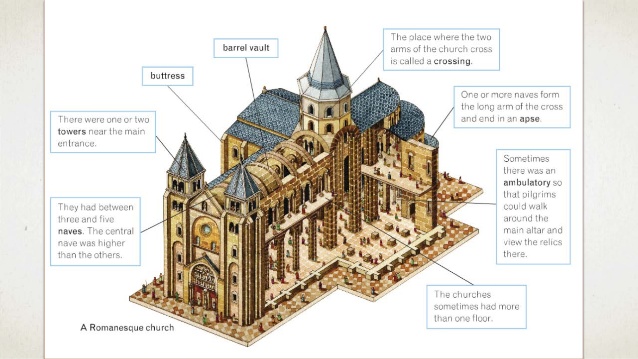

1100 to 1450 — Gothic

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Chartres-528951782-crop-57df6a545f9b586516c98386.jpg)

Early in the 12th century, new ways of building meant that cathedrals and other large buildings could soar to new heights. Gothic architecture became characterized by the elements that supported taller, more graceful architecture— innovations such as pointed arches, flying buttresses, and ribbed vaulting. In addition, elaborate stained glass could take the place of walls that no longer were used to support high ceilings. Gargoyles and other sculpting enabled practical and decorative functions.

Many of the world’s most well-known sacred places are from this period in architectural history, including Chartres Cathedral and Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral in France and Dublin’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Adare Friary in Ireland.

Gothic architecture began mainly in France where builders began to adapt the earlier Romanesque style. Builders were also influenced by the pointed arches and elaborate stonework of Moorish architecture in Spain. One of the earliest Gothic buildings was the ambulatory of the abbey of St. Denis in France, built between 1140 and 1144.

Originally, Gothic architecture was known as the French Style. During the Renaissance, after the French Style had fallen out of fashion, artisans mocked it. They coined the word Gothic to suggest that French Style buildings were the crude work of German (Goth) barbarians. Although the label wasn’t accurate, the name Gothic remained.

While builders were creating the great Gothic cathedrals of Europe, painters and sculptors in northern Italy were breaking away from rigid medieval styles and laying the foundation for the Renaissance. Art historians call the period between 1200 to 1400 the Early Renaissance or the Proto-Renaissance of art history.

Fascination for medieval Gothic architecture was reawakened in the 19th and 20th centuries. Architects in Europe and the United States designed great buildings and private homes that imitated the cathedrals of medieval Europe. If a building looks Gothic and has Gothic elements and characteristics, but it was built in the 1800s or later, its style is Gothic Revival.

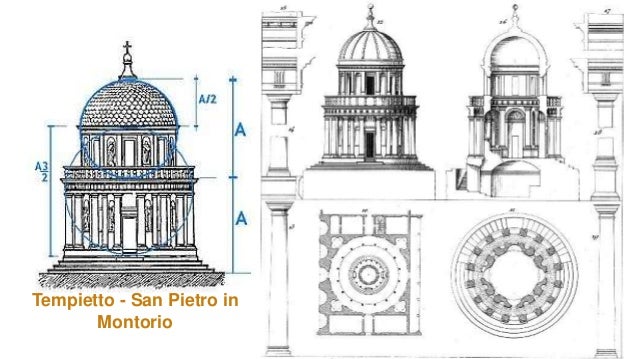

1400 to 1600 — Renaissance

A return to Classical ideas ushered an “age of awakening” in Italy, France, and England. During the Renaissance era architects and builders were inspired by the carefully proportioned buildings of ancient Greece and Rome. Italian Renaissance master Andrea Palladio helped awaken a passion for classical architecture when he designed beautiful, highly symmetrical villas such as Villa Rotonda near Venice, Italy.

More than 1,500 years after the Roman architect Vitruvius wrote his important book, the Renaissance architect Giacomo da Vignola outlined Vitruvius’s ideas. Published in 1563, Vignola’s The Five Orders of Architecture became a guide for builders throughout western Europe. In 1570, Andrea Palladio used the new technology of movable type to publish I Quattro Libri dell’ Architettura, or The Four Books of Architecture. In this book, Palladio showed how Classical rules could be used not just for grand temples but also for private villas.

Palladio’s ideas did not imitate the Classical order of architecture but his designs were in the manner of ancient designs. The work of the Renaissance masters spread across Europe, and long after the era ended, architects in the Western world would find inspiration in the beautifully proportioned architecture of the period. In the United States its descendant designs have been called neoclassical.

1600 to 1830 — Baroque

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/versailles-680783213-crop-5825fc173df78c6f6ac1fc84.jpg)

Early in the 1600s, an elaborate new architectural style lavished buildings. What became known as Baroque was characterized by complex shapes, extravagant ornaments, opulent paintings, and bold contrasts.

In Italy, the Baroque style is reflected in opulent and dramatic churches with irregular shapes and extravagant ornamentation. In France, the highly ornamented Baroque style combines with Classical restraint. Russian aristocrats were impressed by the Palace of Versailles, France and incorporated Baroque ideas in the building of St. Petersburg. Elements of the elaborate Baroque style are found throughout Europe.

Architecture was only one expression of the Baroque style. In music, famous names included Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi. In the art world, Caravaggio, Bernini, Rubens, Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Velázquez are remembered. Famous inventors and scientists of the day include Blaise Pascal and Isaac Newton.

1650 to 1790 — Rococo

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/architecture-rococo-stcatherine-508621707-5bd1e60346e0fb0051580ab2.jpg)

During the last phase of the Baroque period, builders constructed graceful white buildings with sweeping curves. Rococo art and architecture is characterized by elegant decorative designs with scrolls, vines, shell-shapes, and delicate geometric patterns.

Rococo architects applied Baroque ideas with a lighter, more graceful touch. In fact, some historians suggest that Rococo is simply a later phase of the Baroque period.

Architects of this period include the great Bavarian stucco masters like Dominikus Zimmermann, whose 1750 Pilgrimage Church of Wies is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

1730 to 1925 — Neoclassicism

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/architecture-neoclassical-uscapitol-AOC-crop-5ad8089104d1cf00373e9105.jpg)

By the 1700s, European architects were turning away from elaborate Baroque and Rococo styles in favor of restrained Neoclassical approaches. Orderly, symmetrical Neoclassical architecture reflected the intellectual awakening among the middle and upper classes in Europe during the period historians often call the Enlightenment. Ornate Baroque and Rococo styles fell out of favor as architects for a growing middle class reacted to and rejected the opulence of the ruling class. French and American revolutions returned design to Classical ideals—including equality and democracy—emblematic of the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome. A keen interest in ideas of Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio inspired a return of Classical shapes in Europe, Great Britain, and the United States. These buildings were proportioned according to the classical orders with details borrowed from ancient Greece and Rome.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, the newly-formed United States drew upon Classical ideals to construct grand government buildings and an array of smaller, private homes.

1890 to 1914 — Art Nouveau

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/architecture-artnouveau-HotelLutetia-524929510-5ada10eea9d4f9003dbc7da6.jpg)

Known as the New Style in France, Art Nouveau was first expressed in fabrics and graphic design. The style spread to architecture and furniture in the 1890s as a revolt against industrialization turned people’s attention to the natural forms and personal craftsmanship of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Art Nouveau buildings often have asymmetrical shapes, arches, and decorative Japanese-like surfaces with curved, plant-like designs and mosaics. The period is often confused with Art Deco, which has an entirely different visual look and philosophical origin.

Note that the name Art Nouveau is French, but the philosophy—to some extent spread by the ideas of William Morris and the writings of John Ruskin—gave rise to similar movements throughout Europe. In Germany it was called Jugendstil; in Austria it was Sezessionsstil; in Spain it was Modernismo, which predicts or event begins the modern era. The works of Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926) are said to be influenced by Art Nouveau or Modernismo, and Gaudi is often called one of the first modernist architects.

1895 to 1925 — Beaux Arts

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/garnier-parisopera-500191203-crop-58ae60113df78c345b9e61b0.jpg)

Also known as Beaux Arts Classicism, Academic Classicism, or Classical Revival, Beaux Arts architecture is characterized by order, symmetry, formal design, grandiosity, and elaborate ornamentation.

Combining classical Greek and Roman architecture with Renaissance ideas, Beaux Arts architecture was a favored style for grand public buildings and opulent mansions.

1905 to 1930 — Neo-Gothic

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/architecture-neogothic-tribune-71447573-crop-5ad80f3c642dca003683e601.jpg)

In the early 20th century, medieval Gothic ideas were applied to modern buildings, both private homes and the new type of architecture called skyscrapers.

Gothic Revival was a Victorian style inspired by Gothic cathedrals and other medieval architecture. Gothic Revival home design began in the United Kingdom in the 1700s when Sir Horace Walpole decided to remodel his home, Strawberry Hill. In the early 20th century, Gothic Revival ideas were applied to modern skyscrapers, which are often called Neo-Gothic. Neo-Gothic skyscrapers often have strong vertical lines and a sense of great height; arched and pointed windows with decorative tracery; gargoyles and other medieval carvings; and pinnacles.

The 1924 Chicago Tribune Tower is a good example of Neo-Gothic architecture. The architects Raymond Hood and John Howells were selected over many other architects to design the building. Their Neo-Gothic design may have appealed to the judges because it reflected a conservative (some critics said “regressive”) approach. The facade of the Tribune Tower is studded with rocks collected from great buildings around the world. Other Neo-Gothic buildings include the Cass Gilbert design for the Woolworth Building in New York City.

1925 to 1937 — Art Deco

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/chrysler-171575194-56a02f875f9b58eba4af490d.jpg)

With their sleek forms and ziggurat designs, Art Deco architecture embraced both the machine age and ancient times. Zigzag patterns and vertical lines create dramatic effect on jazz-age, Art Deco buildings. Interestingly, many Art Deco motifs were inspired by the architecture of ancient Egypt.

The Art Deco style evolved from many sources. The austere shapes of the modernist Bauhaus School and streamlined styling of modern technology combined with patterns and icons taken from the Far East, classical Greece and Rome, Africa, ancient Egypt and the Middle East, India, and Mayan and Aztec cultures.

Art Deco buildings have many of these features: cubic forms; ziggurat, terraced pyramid shapes with each story smaller than the one below it; complex groupings of rectangles or trapezoids; bands of color; zigzag designs like lightening bolts; strong sense of line; and the illusion of pillars.

By the 1930s, Art Deco evolved into a more simplified style known as Streamlined Moderne, or Art Moderne. The emphasis was on sleek, curving forms and long horizontal lines. These buildings did not feature zigzag or colorful designs found on earlier Art Deco architecture.

Some of the most famous art deco buildings have become tourist destinations in New York City—the Empire State Building and Radio City Music Hall may be the most famous. The 1930 Chrysler Building in New York City was one of the first buildings composed of stainless steel over a large exposed surface. The architect, William Van Alen, drew inspiration from machine technology for the ornamental details on the Chrysler Building: There are eagle hood ornaments, hubcaps, and abstract images of cars.

1900 to Present — Modernist Styles

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Modern-520715465-5871bd185f9b584db3a5843c.jpg)

The 20th and 21st centuries have seen dramatic changes and astonishing diversity. Modernist styles have come and gone—and continue to evolve. Modern-day trends include Art Moderne and the Bauhaus school coined by Walter Gropius, Deconstructivism, Formalism, Brutalism, and Structuralism.

Modernism is not just another style—it presents a new way of thinking. Modernist architecture emphasizes function. It attempts to provide for specific needs rather than imitate nature. The roots of Modernism may be found in the work of Berthold Luberkin (1901–1990), a Russian architect who settled in London and founded a group called Tecton. The Tecton architects believed in applying scientific, analytical methods to design. Their stark buildings ran counter to expectations and often seemed to defy gravity.

The expressionistic work of the Polish-born German architect Erich Mendelsohn (1887–1953) also furthered the modernist movement. Mendelsohn and Russian-born English architect Serge Chermayeff (1900–1996) won the competition to design the De La Warr Pavilion in Britain. The 1935 seaside public hall has been called Streamline Moderne and International, but it most certainly is one of the first modernist buildings to be constructed and restored, maintaining its original beauty over the years.

Modernist architecture can express a number of stylistic ideas, including Expressionism and Structuralism. In the later decades of the 20th century, designers rebelled against the rational Modernism and a variety of Postmodern styles evolved.

Modernist architecture generally has little or no ornamentation and is prefabricated or has factory-made parts. The design emphasizes function and the man-made construction materials are usually glass, metal, and concrete. Philosophically, modern architects rebel against traditional styles. For examples of Modernism in architecture, see works by Rem Koolhaas, I.M. Pei, Le Corbusier, Philip Johnson, and Mies van der Rohe.

1972 to Present — Postmodernism

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/postmodern-220celebrationplace-5663cc0e5f9b583dc3762cde.jpg)

A reaction against the Modernist approaches gave rise to new buildings that re-invented historical details and familiar motifs. Look closely at these architectural movements and you are likely to find ideas that date back to classical and ancient times.

Postmodern architecture evolved from the modernist movement, yet contradicts many of the modernist ideas. Combining new ideas with traditional forms, postmodernist buildings may startle, surprise, and even amuse. Familiar shapes and details are used in unexpected ways. Buildings may incorporate symbols to make a statement or simply to delight the viewer.

Philip Johnson’s AT&T Headquarters is often cited as an example of postmodernism. Like many buildings in the International Style, the skyscraper has a sleek, classical facade. At the top, however, is an oversized “Chippendale” pediment. Johnson’s design for the Town Hall in Celebration, Florida is also playfully over-the-top with columns in front of a public building.

Well-known postmodern architects include Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown; Michael Graves; and the playful Philip Johnson, known for making fun of Modernism.

.jpg)

The key ideas of Postmodernism are set forth in two important books by Robert Venturi. In his groundbreaking 1966 book, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, Venturi challenged modernism and celebrated the mix of historic styles in great cities such as Rome. Learning from Las Vegas, subtitled “The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form,” became a The Ordnance Pavilion by Studio Mutt, 2018 classic when Venturi called the “vulgar billboards” of the Vegas Strip emblems for a new architecture. Published in 1972, the book was written by Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour, and Denise Scott Brown.

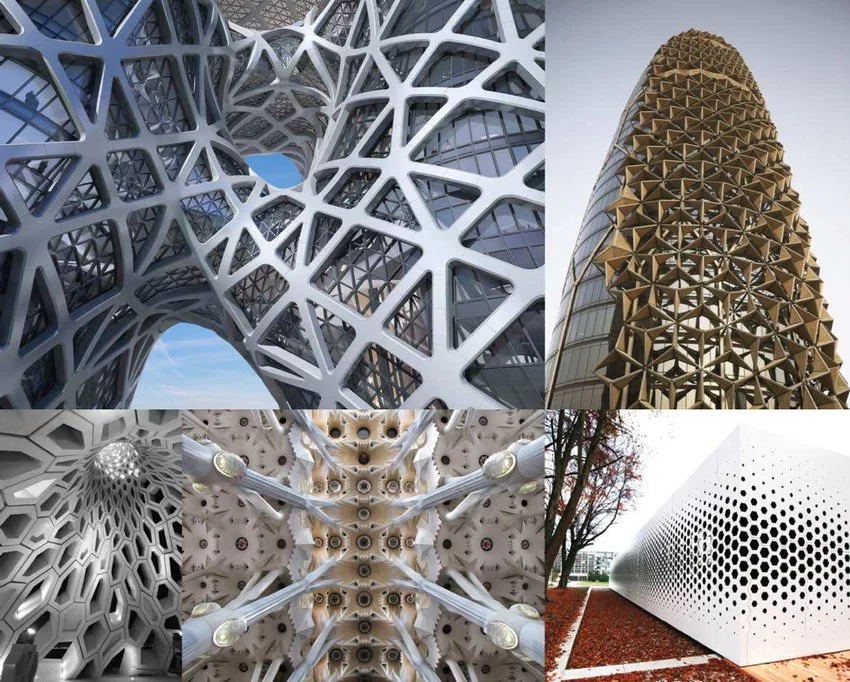

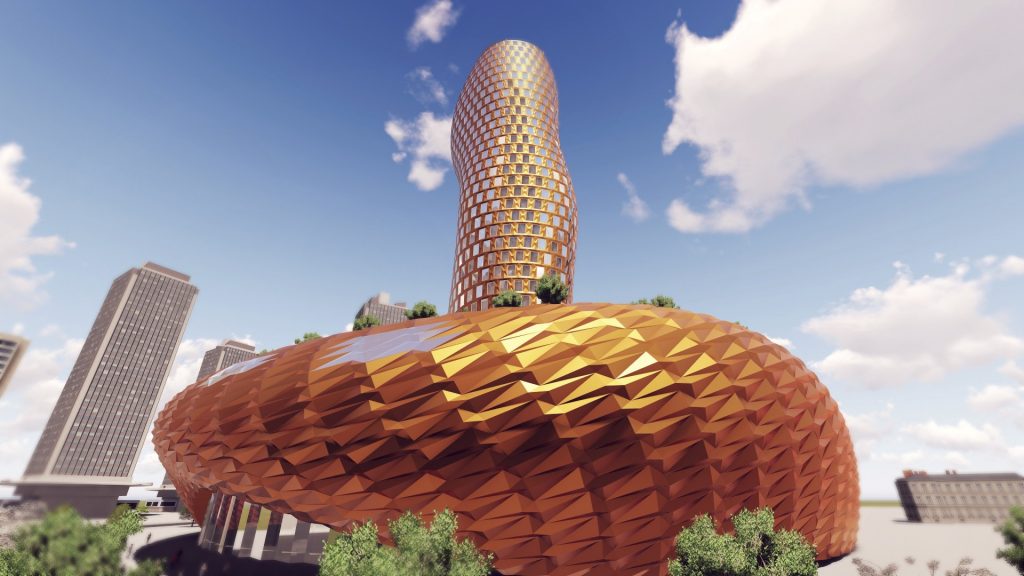

1997 to Present — Neo-Modernism and Parametricism

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/hadid-468889296-57a9ba7a5f9b58974a223c71.jpg)

Throughout history, home designs have been influenced by the “architecture du jour.” In the not far off future, as computer costs come down and construction companies change their methods, homeowners and builders will be able to create fantastic designs. Some call today’s architecture Neo-Modernism. Some call it Parametricism, but the name for computer-driven design is up for grabs.

How did Neo-Modernism begin? Perhaps with Frank Gehry’s sculpted designs, especially the success of the 1997 Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Maybe it began with architects who experimented with Binary Large Objects—BLOB architecture. But you might say that free-form design dates back to prehistoric times. Just look at Moshe Safdie’s 2011 Marina Bay Sands Resort in Singapore: It looks just like Stonehenge.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/StoneHenge_MarinaSands-58c093463df78c353c0d0789.jpg)